Translated from the German by Tess Lewis.

Below, in the river, there was a boulder called the Elephant, round,

with its light-coloured belly facing up. Horsetails swayed on the

bank, stretching their heads toward the water and behind them, bar-

berries glowed on the hedge through the dark tree trunks.

It was late summer. The splendour floated silently past in the

shimmering heat.

Grandfather sat on the Elephant, his ears filled with humming.

The shadow of a thick cloud suddenly spread over the bank,

where the dog hungrily stuck his snout in the earth to fill his mouth

with a cold rat, as flies flew in all directions.

The child climbed up to Grandfather. They sat together in silence for

a time, staring at the water, the fishing rod and the bobber. No fish

had bitten yet. The Elephant was an enchanted place that you some-

times had to seek out, even against your own will.

Sometimes a void opened up there, a hole that grew bigger and

deeper with every blink of an eye, and it was clear: if no one jumped

in and filled the hole, it could swallow everything.

It didn’t take long for the water to reveal this time, too, what it

had to reveal.

Small and still, growing ever smaller, her little brother floated

out on the sparkling river until he was nothing but a tiny speck, until

a wave finally took him under this time too.

And like it did every time, the child’s heart started beating again

like a drumroll.

Grandfather had caught a trout.

The child scrambled down the Elephant quick as a flash to escape

the water and the struggling fish. But the shore was also dangerous

terrain.

The pool at the foot of the alder tree was dry, the croaking

hushed, but loud croaking still filled child’s ears. She clamped her

hands over them and ran quickly toward the house.

***

It’s still early, it’s summer. Grandmother takes the coffee from the

cabinet. She longs for snow.

The cheerful drifts, she says. She loves this other silence.

When she wakes in the morning, much too early because she

couldn’t think the previous day through to the end, then she wishes

it would snow.

We need to go to the seamstress, she tells the child, be sure to

come straight home from school.

The crocodile, the child replies with a smirk.

Sh-sh-sh, Grandmother hisses, grabs the child by the arm and

presses her thumb, as rough as sandpaper, on the child’s face, first on

the left corner of the girl’s mouth, then on the right, smearing the

jam all the way to her earlobes. Grandmother calls this washing your

mouth.

But you’re right, she says to the child, the seamstress does have

eyes like a crocodile. Every time I see her, I think of this. The way it

looked at me, the monster. That was somewhere in Cuba. Behind the

hostel was a sluggish river where it lurked and suddenly it sloshed

onto land like a heavy, wet package. Those alert, beady eyes!

When you’re angry, your eyes get beady too, the child says.

The girl always feels naked when she’s standing in front of the

seamstress, when she pulls out her measuring tape to take the girl’s

measurements.

But I don’t smell like the crocodile, Grandmother says and laughs.

No one else can make blouses and such pretty dresses for the

child out of old shirts.

***

It’s not easy to escape Grandmother. The child’s skin is covered with

imprints from her sandpaper thumbs.

When she takes the child’s hand to drag her somewhere she

doesn’t want to go, she presses her thumbs on the inside of the child’s

wrists and thrusts her here and there, driven by the child’s heartbeat.

Or is it the other way round? Does the child’s heart beat because

Grandmother’s thumb makes it beat? The child wants to pull away

but doesn’t dare. Her heart might stop beating. Grandmother is in

the child’s heart, she has lodged herself in there and boxes the cham-

bers with her broad, rough thumb.

At these times the child hates her grandmother, but there’s no

need for her to have a guilty conscious. Grandmother knows hatred.

It’s a feeling that warms like fire, she says. She doesn’t understand

why hatred has a bad reputation. It sharpens the senses, gets the

blood flowing and simply does one good, she says. Talking about

hatred gives her a pleasant feeling. What would humans be without

hatred! she says. We would be incapable of suffering and loving, we

could not hope for anything better if we are so satisfied and at one with

the world. There would be no art, no books, no discussions, no good

roast, no reconciliation, no arguments and no peace. Only harmony.

Good heavens, she says, can you possibly imagine a more boring

world? Harmony makes you fat and lazy. A little hate is the spice of

life! There is time enough later for cloud cuckoo land. Besides, maybe

that’s just another name for Hell, she says, her face glowing. She

wants the luxury of feeling a little hatred once in a while.

That’s why the child doesn’t have a bad conscience when she

hates and is warmed by her hatred.

But you must save your hatred for important people and things,

Grandmother says, for the rest, it’s not worth the effort. And so, the

child tries hard not to hate the neighbour. She just looks the neigh-

bour in the face, as if she weren’t even there, and doesn’t answer. No

matter how saccharine sweetly the neighbour smiles or complains

to Grandmother that the child is obstinate.

The neighbour is a woman who never means what she says the

way it sounds, Grandmother says. She digs her claws into the super-

ficial as if there were an abyss beneath it. She has two children and

looks as if she still hasn’t ever sniffed a man.

Grandmother, on the other hand, needs the naked truth. She

trusts her own soul absolutely.

Why does the neighbour have a hunchback? the child asks.

That’s because her heart hopped into her back and is no longer

in the right place.

***

It’s different with the crow. She’s distantly related to Grandmother

and so the child is allowed to hate her a little. Before, the crow would

often come into the house and hog Grandfather for hours with her

tales of murder.

Year-in, year-out she wears black dresses and lives in the rust-red

building above the village, but only in summer. In the winter, she

flies to Italy where she has earnings from a bakery.

Murderers stalk the crow. They climb down from the attic and

she is always on guard in and around the house that the beasts don’t

catch her.

She often has to go to hospital in the city when the murderers

have got hold of her and afterwards she would visit Grandfather so

that he could comfort her.

She doesn’t come any more because Grandfather is in Tamangur

and Grandmother doesn’t want to comfort her.

The murderers have never properly caught the crow, only made

her ill, just like the piano teacher who lives in the same building and

comes from Russia, where Siberia is and it’s freezing all year round.

And where people say ‘my heart rattles like a Kalashnikov,’ instead of

‘my heart beats.’

When you sit on a bench in Siberia, you have to get up before

long and go away, otherwise you’ll freeze to it and turn into an icicle.

It’s often very cold in the village, too. Once, when the cat lay in wait

too long for a mouse, its tail froze to the floor and the cat screamed

the way her little brother screamed when he was hungry. And now

the cat has only half a tail.

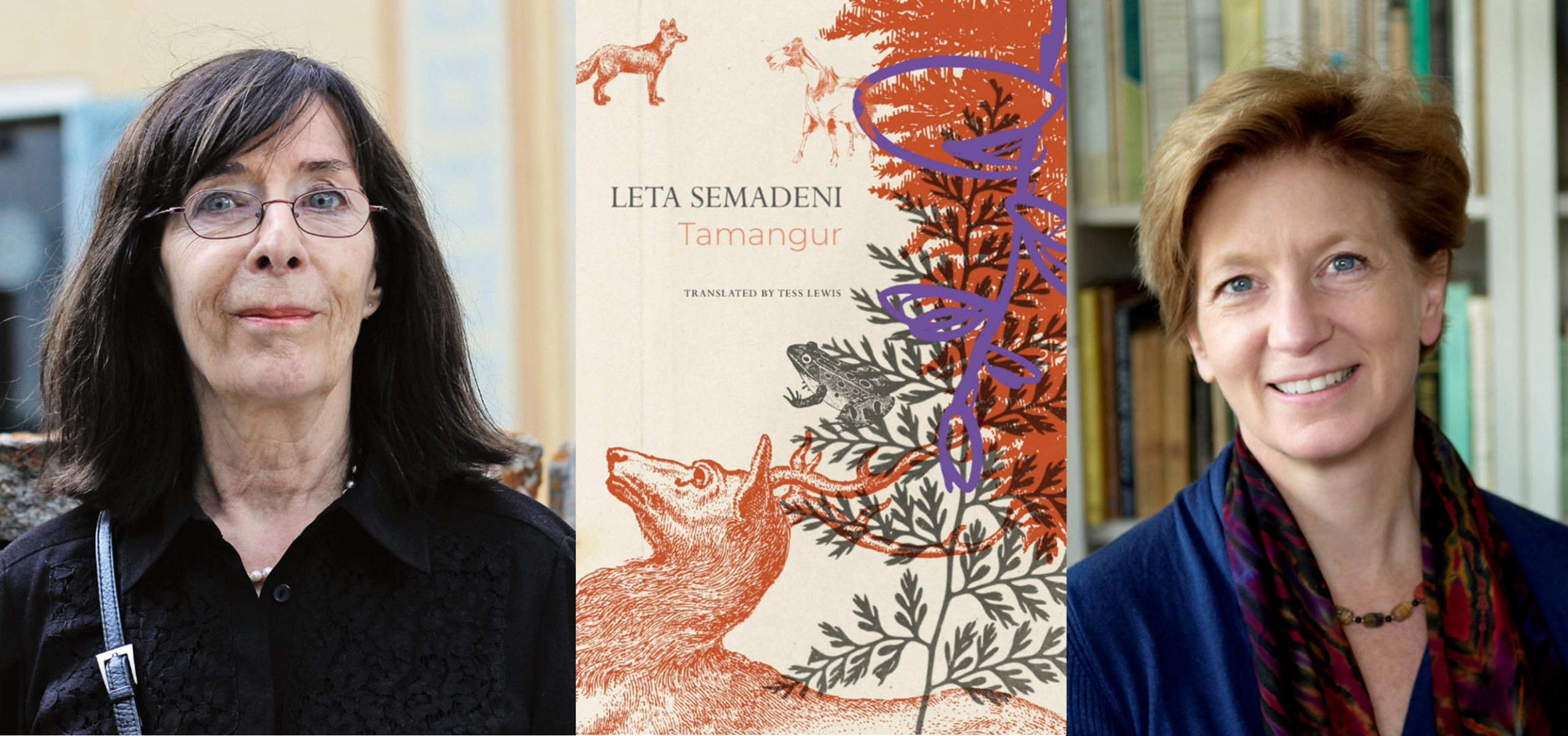

Leta Semadeni was born in Scuol, Engadin in 1944. She studied languages at the University of Zurich and worked as a teacher in Zurich and Engadin. She has held residencies in Latin America, Paris, Zug, Berlin, and New York. Since 2005, she has lived in Lavin as a freelance writer. Writing poetry in Romansch and German, her collections have won multiple awards, including the 2011 Literature Prize of the Canton Graubünden. Her debut novel, Tamangur, earned the 2016 Swiss Literature Prize and has been translated into several languages. In 2023, she received the Grand Prix for Literature, the most prestigious Swiss literary prize.

Tess Lewis translates from French and German, including works by Peter Handke, Jean-Luc Benoziglio, Klaus Merz, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, and Pascal Bruckner.

This excerpt from TAMANGUR was published by permission of Seagull Books. Copyright © 2015 Leta Semadeni; translation copyright © 2025 Tess Lewis. Photo credit Leda Semadeni: Georg Luzzi.