Translated from the Japanese by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda.

Oku Aizu

On the Privilege of Linguistic Immigrants

A few years ago, I went on a trip to Oku Aizu, a region in the western part of Fukushima, with a few friends of mine from the publishing world. Mitsuhiro Muroi, a writer and literary critic who is from the area, explained to us that the closer you go to the center of the Japanese archipelago, the narrower the spaces between mountain ranges, and the less flat the land. As I listened to him, an image suddenly came to mind of Japan as a living organism with folds and wrinkles. In one of Muroi-san’s books, he also mentions that in Oku Aizu, intonation doesn’t really exist in everyday speech. In “standard” Japanese, if you say the word hashi with an emphasis on the first syllable, it means “chopsticks” but if you emphasize the second syllable, it means “bridge” or “edge.” Since people in Oku Aizu don’t make this distinction, unexpected possibilities open up: tango could mean “word” or an Argentine dance. Samba could mean a “midwife” or a Brazilian dance.

This reminds me of an accidental connection I once made between the German words Brücke (bridge) and Lücke (gap, blank) as a result of my struggle to distinguish between the consonants “R” and “L.” My conflation of these words eventually lead me to the idea that discovering the gaps (Lücke) between cultures was much more interesting than building bridges (Brücke) between them. In this way, two seemingly unrelated words (tango) were brought together by my native phonetic system, and began to tango together. From there, a midwife (samba) came along and a new idea was born. This is the privilege of linguistic immigrants. It is an art that may seem easy at first glance but is in fact quite difficult to imitate for those who are confined to a single language. Of course some may say, out of spite of course, that I’m simply making puns.

Allegedly, everyone is born with a latent ability to understand and speak any language. This means that acquiring a mother tongue inherently kills off the possibility of speaking any other language at a native level. Experiments have shown that if a child is exposed only to Japanese, it loses the ability to distinguish between “L” and “R” as early as six months of age. Of course, it’s not impossible to learn this later in life, but it’s certainly not easy. On the other hand, if your mother tongue is a European language,

you lose, at least temporarily, the ability to hear inflections in Chinese and other languages, and your ability to memorize Chinese characters becomes progressively slower.

It’s amazing to think that a newborn child has the latent ability to speak any language. However, if it maintained this latent ability forever, it would never be able to speak any language at all. To take this conclusion to its logical extreme, then we could say that acquiring a mother tongue implies the destruction of all other possibilities. In a way, it seems a little wasteful.

Perhaps the desire to learn another language as an adult is simply a nostalgic yearning for that time in infancy when we had completely unrestricted movement over our tongue and lips. Reading aloud from a foreign language textbook as we move our tongue in ways that it usually never moves in everyday life, searching out those places in the mouth where the tongue otherwise never touches—isn’t this in essence a kind of dance? Something inside me longs for a tongue that is infinitely flexible, bends in every direction, stretches, shrinks, strikes and breathes, a tongue that dances about in search of freedom without having to produce a single meaningful sound. But if I actually had a tongue like that, no one would understand me. Which is why I’m left with no choice but to pretend I am a rigid monoglot and go around exchanging meaningful phrases with people around me. Still, behind this facade is a hidden impulse toward a free tongue.

*****

Weimar

Small Languages, Big Languages

In 1999, I went to Weimar for the the 250th anniversary of Goethe’s birth. They invited me to be part of a panel on the concept of “world literature” which Goethe came up with, and asked me to talk about what I thought world literature meant in the 21st century. The first thing that came to mind was translated literature. I wasn’t interested in thinking about world literature as opposed to national literatures, but I was interested in the way words change the moment they cross national borders. So I

talked about how world literature might be understood as translated literature, since the only way we can access “world literature” at all is through translation. Translation is often thought of as a necessary evil. And although the question of translation had rarely been seriously considered in relation to literature more broadly, I decided to proceed from the idea that world literature was first and foremost translated literature.

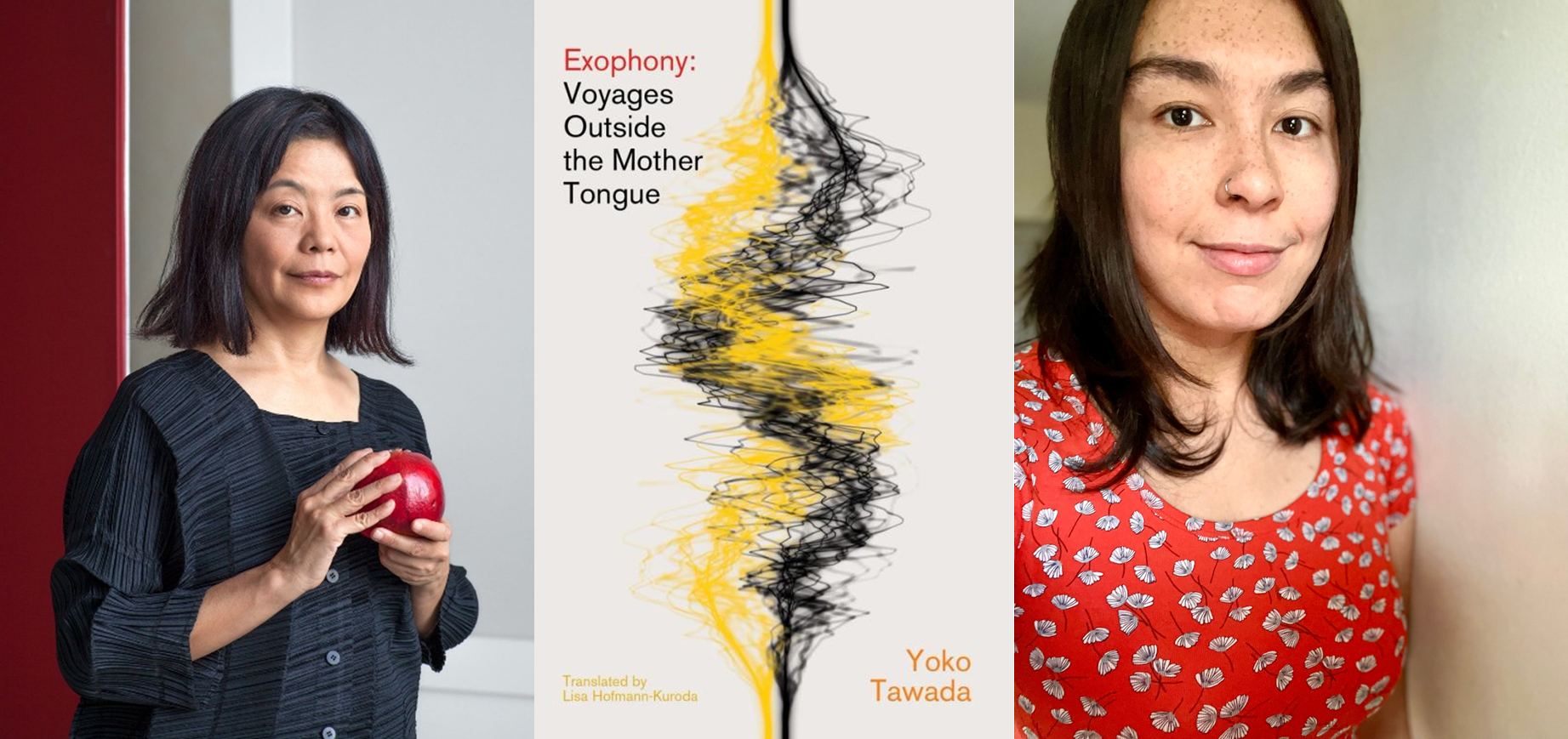

Yoko Tawada was born in Tokyo in 1960, moved to Hamburg when she was twenty-two, and then to Berlin in 2006. She writes in both Japanese and German, and has published several books—stories, novels, poems, plays, essays—in both languages. She has received numerous awards for her writing including the Akutagawa Prize, the Adelbert von Chamisso Prize, the Tanizaki Prize, the Kleist Prize, the Goethe Medal, and the National Book Award. New Directions publishes her story collections Where Europe Begins (with a preface by Wim Wenders) and Facing the Bridge, as well her novels The Naked Eye, The Bridegroom Was a Dog, Memoirs of a Polar Bear, The Emissary, Scattered All over the Earth, Paul Celan and the Trans-Tibetan Angel, Suggested in the Stars, and forthcoming in autumn 2025 is Archipelago of the Sun, the final novel in her Scattered trilogy.

Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda is a literary translator. Her work includes Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s Kappa (New Directions, 2023), Yuko Tsushima’s Wildcat Dome (FSG, 2025), Natsuo Kirino’s Swallows (Knopf, 2025) and Yoko Tawada’s Exophony (New Directions, 2025) among others. Born in Tokyo, raised in Texas, she now lives in New York City.

“Oku Aizu: On the Privilege of Linguistic Immigrants” by Yoko Tawada, translated by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, from EXOPHONY, copyright ©2003 Yoko Tawada, translation copyright © 2025 Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.

Photo Yoko Tawada by Nina Subin; photo Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda by Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda