Translated from the French by Aqiil M. Gopee with Jeffrey Diteman.

Foreword (by Aqiil Gopee)

…The story in this book might come from an island, but it is not insular. Its translation for the first time into English aims at dismantling the hegemony that North America seems to have established over the historiography of slavery. The transatlantic trade route was but one of the many itineraries of human trafficking that involved the African continent, and it is imperative that we break the historic silence surrounding trans-Saharan, Indian Ocean, and Mascarene (including the islands of Mauritius, Réunion, and Rodrigues) economies of enslavement. This goes beyond contextual comparison, as those networks were intimately connected, their histories shared, and based upon the shattering, capture, and estrangement of the same families, the same tribes, the same peoples….

*****

The Plantation

Nearly two hours had passed since the silent parting of our four companions. A milky glow, the gauze of dawn, had begun to appear, vaguely wafting over the edges of the Orient.

Like a sylph heralding the coming of day, the white-tailed tropic bird had left its nest. It sang the tidings of daybreak, carrying its melody from leaf to leaf, from branch to branch.

The blackbird was also waking up. Its voice softly echoed across the morning winds as it replicated the cheerful report, as diligently as the honeybee suckling the treasures nestled inside granadillas and rose-apples.

It was spring, but spring, summer, winter, autumn, what does it matter in the tropical island’s climate? Heat, fruits, flowers, and lush greenery abound year-round.

The day kept stretching and swelling. It lifted a sweet, pleasant, invigorating, blissful, soft breeze that drifted, dense with fragrances, inducing in its wake an ineffable drunkenness. It felt like the divine breath of creation and of life itself!

The sun was about to rise. Shimmering clouds, like seraphs, proclaimed its coming. Everything seemed to hold its breath in anticipation. Finally, as it burst forth in a blaze of light, revealing its radiant countenance, a general symphony erupted.

The air was filled with the droning wings of the golden fly; the waxbill’s little jolting, chromatic shriek; the canary’s arias and flourishes; and the turtledove’s cooing, like the serenade of a young girl in love.

Everything was singing: the waterfall, as it cascaded down the mountain; the pristine stream, caressing the green grass; the droplet of dew, shimmering over leaves and beaming inside flowers; the butterfly, frolicking and fluttering its colorful wings over each perfumed corolla; the swaying palm tree, its emerald fronds swishing in the breeze; the guava tree and its myriad pink blooms; the birds, the insects, the trees, the whole of nature—yes, everything was music to the ears and a delight for the eyes, everything was expressing bliss in this paradise, except, of course, for the miserable Negro . . .

Alas! Indeed, only him! For this beautiful and blessed hour brings him no joy, but instead snatches him away from the tender dreams of the night and plunges him into the harsh reality of his doomed fate. It serves as a cruel reminder that he is a slave, destined for another day of labor, exhaustion, and brutal beatings. It is the sorrowful hour when his voice rises to the sky, not in prayer, but in lament! It is the wretched hour when his body contorts in agony as he endures the lashings at the quatre-piquets! It is the hour when the master, after receiving reports of the previous day’s work, unleashes terrible punishments—his own twisted way of greeting the sunrise!

Now, let us take a closer look at the landscape before us. Just ahead, past some master’s beautiful house, which overlooks a grand avenue adorned with pineapple plants, stands a bustling sugar mill with crushing rollers operating at full steam. Next to it is a field of sugar beets, swaying their innumerable flower stems and delicate plumes and stretching off into the distance as far as the eye can see. Their constant motion gives them the appearance of a formidable army encamped between the mountain and the estate.

To the right, we behold symmetrical rows of clove trees and nutmeg trees adorned with purplish nuts. They stand firmly in a broad, elongated expanse of soil, flanked by storehouses, barns, and small slave huts, built with thatch and leaves. A line of towering tropical trees forms a protective hedge, separating this area from the sprawling cocoa trees, distinguished by their long, red, ribbed fruits. On the other side are flourishing coffee bushes, each adorned with clusters of ripe berries that weigh heavily on their branches.

To the left, there are a few straw huts nestled among green hedges. We then encounter the sheepcotes, stables, and hen-houses as the vine- and flower-covered alleys unfurl before us. Further on, a diverse array of gardens emerges, leading to the grand orchard divided by a branch of the river. In sum, we are on one of those colonial estates that are so rich and varied in sights and produce that they cannot quite be described.

However, let us now turn our gaze amidst this abundance and opulence, and behold the wretched state of the slaves—naked, emaciated, and starved—forced to toil like beasts of burden! Our attention is drawn to the platform, at the heart of the estate, where three men are tied up, their bellies pressed against the earth, their limbs outstretched. With long whips in hand, others relentlessly lash them, driven by the menacing commands of the overseer and the master. Blood spills forth! Flesh is torn asunder! Yet not a cry, not a moan escapes their lips! Is there, inside of these men, something mightier than pain? Undoubtedly, within their hearts, myriad emotions intertwine, granting them solace and fortitude in the face of their torment. Otherwise, they would not be enduring such torture in silence, watching, with the fortitude of martyrs, the gates of an unseen heaven opening right in front of them!

But the beatings have ceased. Where are they taking those three unfortunate souls, whom we have already recognized as three of our comrades from the night before? It’s the worst place imaginable—a dungeon, built behind the sugar mill, now opens ominously before them! It is a dismal cell, shrouded in darkness and reeking of decay. But it is not enough to entomb them—they are locked in the stocks, their feet clamped between two large planks, which, purposefully designed to inflict such torture, serve as the resident devils of this infernal abode! Pain married to despair! And yet, not a word has yet escaped from their tortured breasts! Finally, the perpetrators of the master’s orders depart. The Amboilame breaks the silence and, addressing his two companions, says, “I’m sorry, brothers!” with pain in his voice, and as if he were himself either immune to, or guilty of their affliction. He goes on, “Yes, I’m sorry! I was wrong to urge you to return to this cursed plantation . . . ”

The Antacime paused and let out a deep sigh—a gesture that conveyed more in that moment than any words could express. The Sçacalave did not seem to have heard anything, but a stream of muffled sounds came out of his mouth, among which certain words could be discerned: “Blood . . . cell . . . stocks . . . revenge!” This last word was proclaimed so vehemently, in such a roaring tone, that the Amboilame felt the need to calm his friend down. He said:

“Yes, brothers, I was wrong . . . but who could have foreseen that the despicable overseer would notice our absenceand inform the master?”

The Sçacalave, once more, appeared oblivious, and sharply repeated: “Blood . . . cell . . . stocks . . . revenge!” Headded, in a jeering, rageful tone, “Never mind! No revenge! Let’s keep bowing down and kissing the feet of the masters who slaughter us!”

“Yes, they are butchers,” said the Amboilame, still speaking with measured reserve, “but, brothers, let’s be patient: we will break free from their grasp. Whether it’s today, tomorrow, or someday in the future, we shall ultimately achieve . . . ”

“Alas!” interjected the Antacime, his face contorted in regret. “Our Creole brother made a wiser choice by not coming back here with us! He wasn’t beaten, nor is he confined in a cell or the stocks! He’s free in the woods! He’s happier than any of us!”

“You should not say such things, Antacime brother!” answered the Amboilame in a soft, yet admonishing tone. “Understand that our Creole brother is now a maroon, and he might face the threat of being killed or arrested! Yes, we have been beaten, confined in cells, and put in stocks, but what’s done is done. While the threat of such a fate still looms over him, along with that of other greater misfortunes, we, for the time being, have nothing further to fear. We’re back where we started, that’s all. Because, once we escape from here, we’ll resume our initial plan, and let them try to catch us this time! The little boat still waits for us, and we’ll sail away . . . ”

As he finished his sentence, they heard the sound of footsteps and the rattling of keys from outside. The Amboilame fell silent.

What had become of the Black Creole now? Was he truly in a better place?

Louis Timagène Houat was a French writer and physician. Originally from Bourbon Island, now known as La Réunion, he was the author of the first novel in Réunionese literature, Les Marrons, which he published in Paris in 1844.

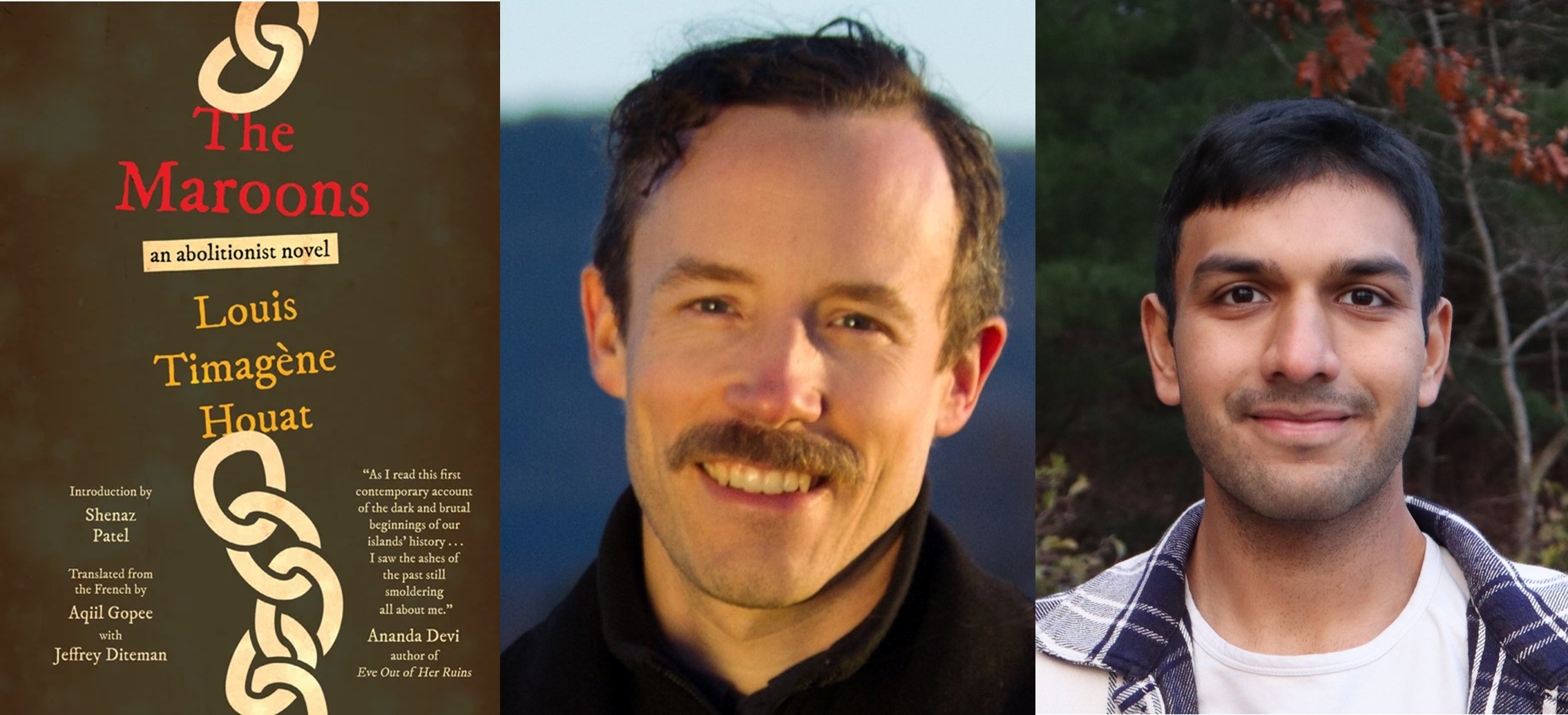

Aqiil M. Gopee is a Mauritian writer and poet with degrees in religion from Amherst College and Harvard, where he also trained in archaeology. He has published numerous short stories and poems in Mauritius, France, and the US, having won the 1st prize of prestigious Prix du Jeune Écrivain in 2023 for his short-story “Insectarium,” published by Buchet-Chastel (Paris). He reads classical Arabic, Attic Greek, Akkadian, and Egyptian, and along with a first novel, he is currently working on a literary translation of the Qur’ān.

Jeffrey Diteman is a literary scholar and translator working in French, Spanish, and English. He has translated the writing of Pablo Martín Sánchez, Raymond Queneau, and Amalialú Posso Figueroa, and regularly translates journalism and children’s literature. His academic research focuses on depictions of cross-cultural influence in narratives of extended kinship from Latin America.

This excerpt from THE MAROONS was published by permission of Restless Books. First published as Les Marrons by Ebrard, Paris, 1844. English translation copyright © 2024 Aqiil M. Gopee with Jeffrey Diteman.